Realising My Own Migration Story

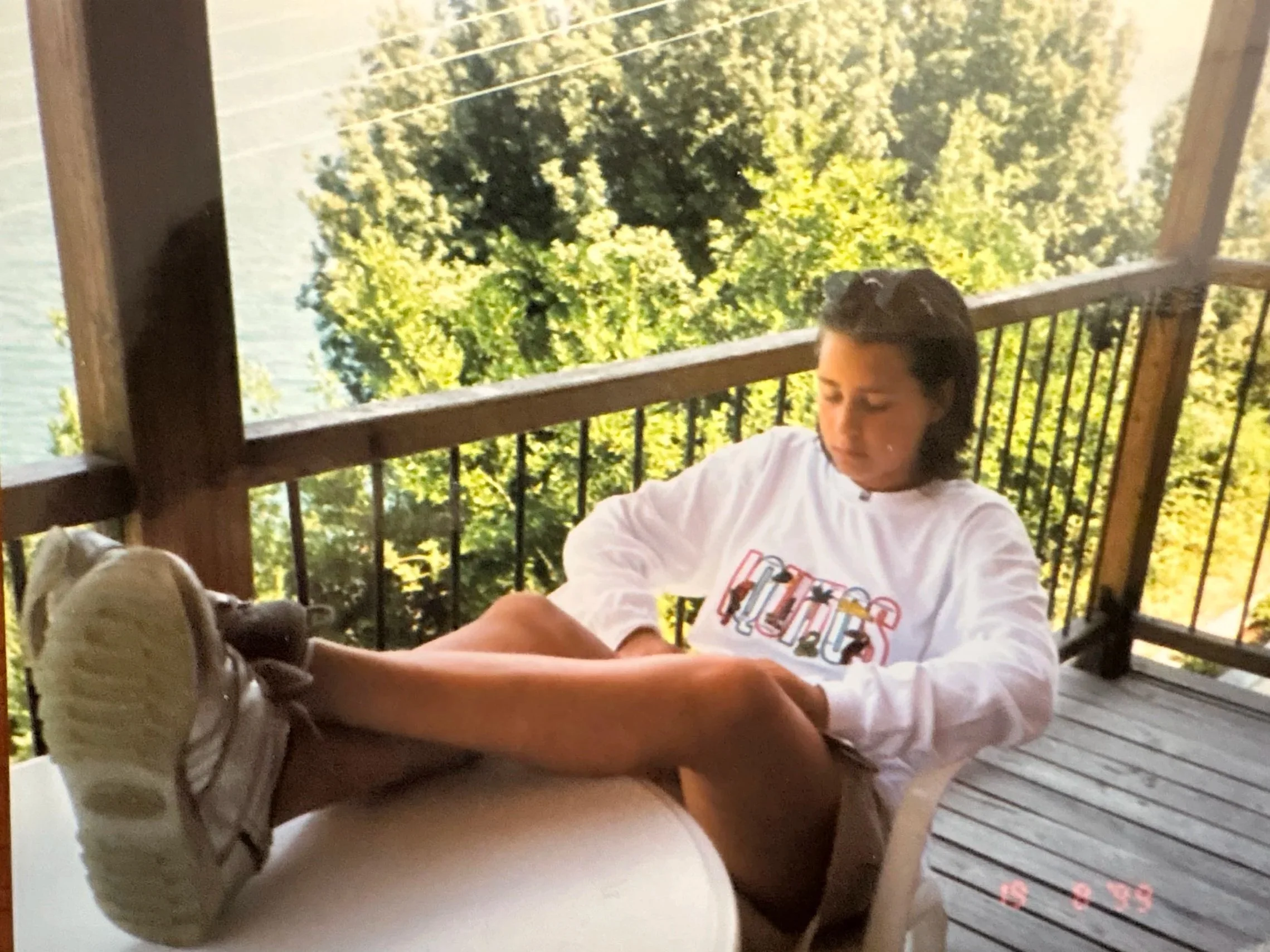

Aged 14, wearing a t-shirt from Iquitos, where my parents lived.

While working with the Migration Museum on a film project at the Museum of Liverpool, something surprising happened. In the middle of interviewing others about their journeys, someone turned to me and said, “But you have a migration story too.”

It stopped me in my tracks.

Like many of us, I’ve always thought of migration as something “other people” had done, my dad, my grandmother, my great-grandparents. But I’d never really claimed it as part of my own identity. Yet when I traced it back, I realised my entire existence is because of a series of journeys across continents, generations, and loves that spanned oceans.

Me & my Grandparents in 1986

My grandmother, Sally, was born in Peru to an English mother from Saltburn and a Peruvian father, Aurelio, who had studied at Edinburgh University. She later fell in love with an Englishman, Rodney, and in 1970, she left Peru with her children, including my dad, who was just 17, to start a new life in the UK.

Years later, in Blackpool, my dad met my mum. She was also 17, and at 21 she made her own leap, moving to the Peruvian Amazon to be with him. That’s where I was conceived, in Iquitos, though I was born in Blackpool. Technically, I’m a seaside baby. But my story is tangled up with Peru, with Scotland, with England, with all the places my family carried in their hearts.

Growing up, we celebrated Peruvian Independence Day, cooked food that smelled like the Amazon and tasted like home, and told stories that stitched together two very different worlds. But I’ve always felt a little in-between. In Peru, I was “the Brit.” In Britain, I was “the Peruvian’s daughter.” I speak very little Spanish, but I’m entrenched in the culture, and yet I don’t feel fully either British or Peruvian. I’m somewhere in the middle like ceviche served with a stick of rock. And that’s okay. Actually, it’s kind of brilliant.

Newspaper clipping from 1985 announcing the return of my parents and their marriage.

Working with the Migration Museum gave me the space to see that this in-betweenness is the story. It’s what migration is, not just the crossing of borders, but the ways identities shift, merge, and reinvent themselves.

And with everything happening in the news right now, the way migration is spoken about, debated, and politicised. I feel more than ever that I need to tell my story. To say: I came to exist because of migration. My creativity, my perspective, my voice as a filmmaker all grow out of it.

Paddington Bear first appeared from ‘darkest Peru’ in October 1958, in A Bear Called Paddington, written by Michael Bond.

Image attributed to Banksy

This isn’t just my family history. It’s my present, and it’s my future work. I want to make films that reflect the humour, the heartbreak, and the humanity of migration. Because behind every headline is a story like mine. One that’s complex, messy, joyful, and deeply human.

So yes, I’m from Blackpool. But I’m also from Iquitos, from Saltburn, from Lytham and Lima, Edinburgh and everywhere in between. And I’m finally ready to own that.

In Production: From Ceviche to a Stick of Rock marks a natural next step in Natasha’s filmmaking journey, co-producing her first feature-length documentary alongside Gareth Lang and their company A Few Good Things. The duo are currently seeking development and production funding to bring this intimate, character-driven film to life. Rooted in questions of identity, migration and belonging, the film blends humour, food and personal history to explore what it means to live between cultures.